19. How One of the First Asian-American Women Lawyers Lost and Regained Her Citizenship (part 1)

Sau Ung Loo Chan lost her citizenship when she married a Chinese man who actually was a U.S. citizen but could not prove it

I have researched a lot of amazing stories of Asian-American legal history, but this one may be my favorite. I discovered it in a footnote and wanted to know more.

Sau Ung Loo Chan was one of the first Asian Americans to graduate from Yale Law School, and she was also one of the first women to do so. And she brought her training and drive to winning perhaps the most important case of her life – proving that her husband was an American.

The case was rooted in family tragedy and drama that began long before she met her husband, Chan Hin Cheung, as well as the complicated racial restrictions in naturalization law in the early 20th century.

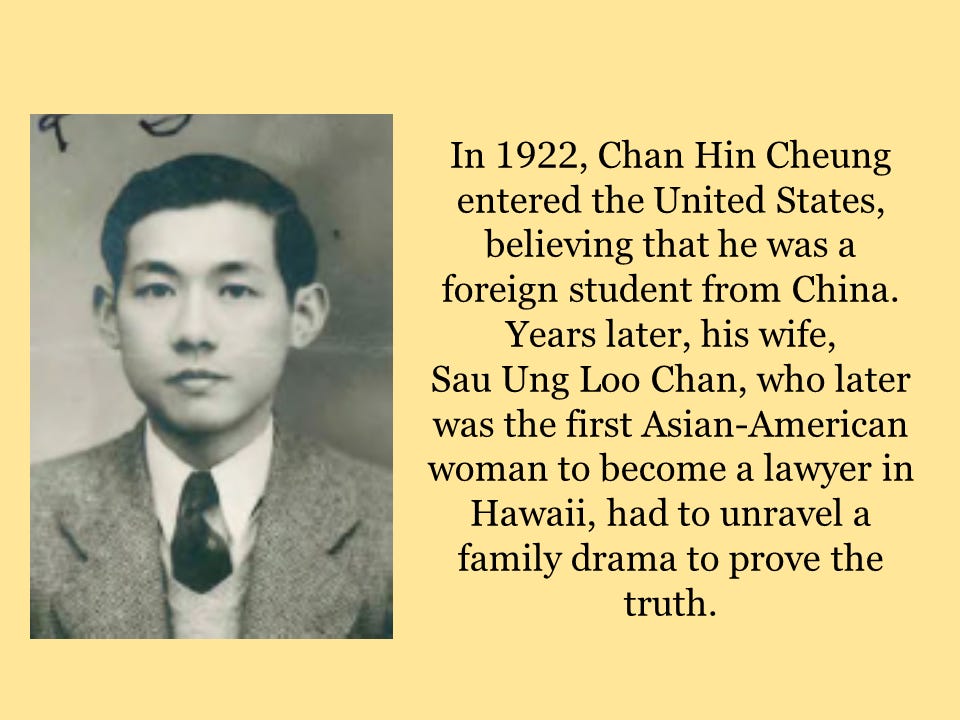

Chan was born in San Francisco in 1906, but the San Francisco earthquake ruined his father’s health and finances, so the family went to China in 1907 and his father died soon afterwards.

Chan grew up in China but wanted to go to the United States to study at Phillips Academy. His mother was worried that he would not return to her, so she let him believe that he would be a foreign student in the United States, not a native-born citizen returning home.

Soon upon arrival, he began to suspect that he had been born in the United States. But he did not know until 1927, when he confronted his mother in China and she admitted the truth.

He tried to clear this up with U.S. immigration authorities in 1928, but they were suspicious and concluded that he was an “impostor and is seeking a return certificate through fraud and misrepresentation.”

Clearing up his citizenship became a priority after he met Sau Ung Loo, a Chinese American who was born in Hawaii and was then attending Yale Law School. Marriage could have serious legal consequences for her – U.S. law at the time stripped American women of their citizenship if they married a non-citizen. This law reportedly had been designed to punish rich American women who married European men with titles (think Downton Abbey), but the law severely impacted Asian-American women who married Asian-American immigrant men.

They decided to go to China together to find evidence of his birth, but they ran into trouble. While he had been in the United States, Chan’s mother had picked out a Chinese girl for her son to marry, and she refused to help prove her son’s citizenship and threatened to never speak with him again unless he broke off the engagement with Sau Ung.

Despite all the legal and familial consequences, Chan Hin Cheung and Sau Ung Loo married in Hong Kong in 1929. But they did not give up hope.

“You knowing how thoroughly Americanized my wife is and the value she places upon her U.S. citizenship – we being absolutely alike in this respect – I need not stress upon the importance of our having our status definitely cleared,” Chan wrote in a 1931 letter.

And so Sau Ung Loo Chan got to work. What she did, and how she won, I’ll cover in part 2.

Sources: I learned about this case in Leti Volpp’s excellent article “Divesting Citizenship: On Asian American History and the Loss of Citizenship Through Marriage,” 53 UCLA Law Review 405 (2005). Footnote 179 referenced Sau Ung Loo Chan, and I had to find out more! I managed to get the case file for Sau Ung Loo Chan’s husband from the National Archives, thanks to a very helpful archivist there. There is a chapter on Sau Ung Loo Chan in Called from Within: Early Women Lawyers of Hawaii, edited by Mari J. Matsuda. I also consulted an oral history of Sau Ung Loo Chan at the Yale Law School, thanks to the help of Jane Park! Please note that there are some inconsistencies in these sources - I have attempted to reconcile them based on my experience as a lawyer and journalist and generally have gone with the archival case records. Thanks also to Phillips Academy, the great school which Chan Hin Cheung attended in the 1920s and I attended in the 1990s, and which has made its old yearbooks available online – seeing Chan’s yearbook entry helped me determine when he learned the truth about his birthplace. For more background on how women’s citizenship were affected by federal laws, see Meg Hacker, “When Saying ‘I Do’ Meant Giving Up Your U.S. Citizenship,” available here.

About the Author: I am a lawyer in Chicago who was previously a federal prosecutor and a newspaper reporter.