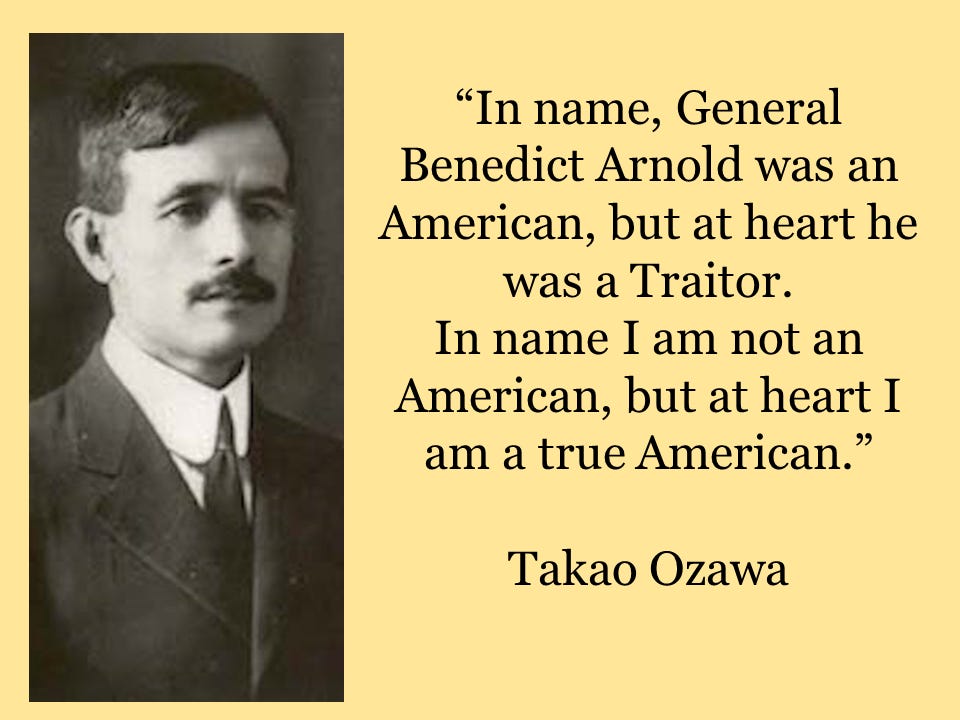

3: "I am pure Japanese, but my heart is American."

Takao Ozawa represented himself while seeking U.S. citizenship, ultimately losing in a 1922 case because he was not "white" under the law

“I am pure Japanese, but my heart is American,” Takao Ozawa told a federal judge in 1915.

He had lived in the United States for most of his life. He thought more of the United States than of Japan, and he was grateful to the United States for the education that he had received. If the United States and Japan ever went to war, he said that he would fight for the United States.

Unfortunately, federal law in the early 20th century restricted citizenship to “free white persons” or those of African nativity or descent, so his petition for citizenship was denied.

Ozawa was working at the time as a salesman in a dry goods department in Hawaii. Even so, he represented himself in federal court, writing lengthy briefs that were deep, creative dives into the meaning of the word “free,” legislative history, the history of racial classifications, and inconsistent applications of the law. (He even used charts, which I think more lawyers should use now!)

Federal Judge Charles Clemons ruled against Ozawa but clearly wished he could have ruled otherwise: “It is indeed a pity that a man so eminently qualified morally and intellectually may not have his earnest desire to become one of us. I cannot speak too highly of his briefs. They evidence more originality, more thought, more thoroughness than many of the briefs of members of our own bar.”

The judge also rejected the government’s attempt to attack Ozawa’s moral fitness. Ozawa had said in a brief that racist laws could hurt U.S. relations with Japan and maybe lead to war. A government attorney said that Ozawa was “threaten[ing] the United States with the government of his own country Japan if he is not allowed to become a citizen of the United States.” Ozawa defended himself, and the judge agreed with him.

Ultimately, Ozawa’s case went to the United States Supreme Court. He had counsel this time, but even so the Supreme Court ruled against him in 1922.

By that time, Charles Clemons had left the judicial bench and he let loose in an op-ed. “It is absurd, of course, that a man must be either ‘white’ or ‘of African nativity … (or) of African descent,’ as the statute reads, in order to become a naturalized American citizen. And it is absurd, because there is really no such thing as a ‘white’ person. The nearest we ever get to cuticular whiteness is, as every undertaker knows, when we have ceased to count as voters; in other words, when we are in our coffins.”

Later, Ozawa and his wife opened a dry goods store, which is still in business today.

When World War II came, Ozawa had passed away and could not fight for the United States as he had once vowed, but his only son could. Sgt. George Yoshio Ozawa served in Europe and was killed in action in Italy. He was 25.

Congress finally eliminated race as a factor for naturalization in 1952.

Sources: “Decision Held Up in Citizenship for Japanese,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, January 30, 1915. “Cannot Speak Too Highly of Ozawa’s Briefs,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, March 28, 1916. “Race Lines and Color Lines,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 15, 1922. Information about George Ozawa’s military service is online at https://www.100thbattalion.org/wp-content/uploads/Ozawa-George-Yoshio.pdf

About the Author: I am a lawyer who used to be a federal prosecutor and a journalist.