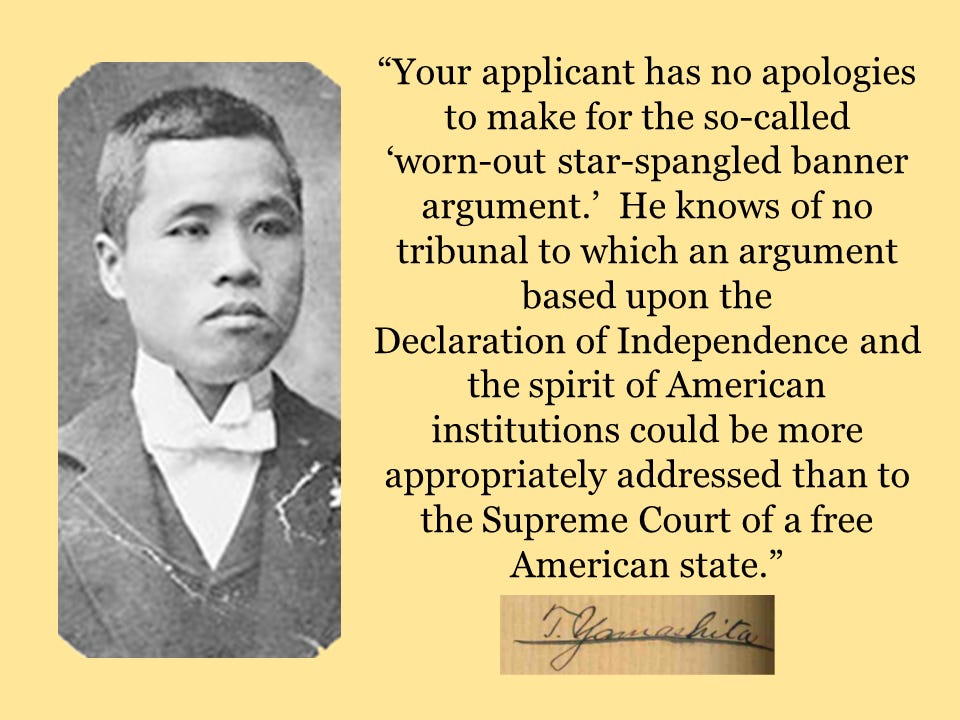

5: "No apologies to make for the so-called 'worn-out' star-spangled banner argument"

Takuji Yamashita challenged racial restrictions twice - first at the Washington Supreme Court in 1902 and then at the United States Supreme Court in 1922 - and then was incarcerated during WWII

Takuji Yamashita could have been one of the greatest Asian American lawyers, but he never got to be a lawyer – at least, not during his lifetime.

He had come from Japan to the United States when he was a teenager, hoping to bring honor to his family and “work for the public good.”

“If my plans to succeed in America fail and I die in a foreign land … I will not be bitter,” he wrote before leaving Japan. “If I become bitter about something, it would be my own intellectual shortcoming.”

He graduated from the University of Washington’s law school, where he had excelled at moot court, and he passed the bar examination.

But when he tried to join the state bar, Washington State’s Attorney General invoked federal law preventing people who were not “white” from becoming citizens and dismissed his attempts to invoke American ideals as “worn out star spangled banner orations.”

Yamashita, then 27 years old and representing himself, double-downed in his reply brief: “Your applicant has no apologies to make for the so-called ‘worn-out star-spangled banner argument.’ He knows of no tribunal to which an argument based upon the Declaration of Independence and the spirit of American institutions could be more appropriately addressed than to the Supreme Court of a free American state.”

In 1902, the Washington Supreme Court ruled against Yamashita because he was not white.

He then went into business but again faced restrictions because he was not white. Washington’s alien land law allowed only U.S. citizens to own land, but he tried getting around this with a legal solution – he formed a corporation. But in 1922, the United States Supreme Court ruled against him when it also decided the case brought by Takao Ozawa.

Despite losing in two high courts, Yamashita persevered in America, working and raising a family.

And then he was incarcerated with other Japanese Americans during World War II, and his family lost everything while they were incarcerated.

This man who showed such promise as a lawyer spent his final working years as a housekeeper. And yet, despite everything Yamashita went through, he “never complained,” one friend said. “He was never bitter.”

Yamashita never got to see his arguments carry the day, but they eventually did. In 1952, Congress ended all racial restrictions on naturalization. In 1966, Washington voters repealed the restrictions on foreigners owning land. In 1973, the United States Supreme Court held that non-citizens must be allowed the opportunity to become lawyers.

And, in 2001, the Washington Supreme Court heard a new petition to admit Yamashita posthumously to the state bar. “We are free to consider the petition before us anew and from a contemporary viewpoint, recognizing that those words in our pledge of allegiance ‘justice of all’ truly mean ‘all’ and not ‘some,’” the chief justice said.

This time, the petition was granted.

Sources: One main source for this article is Steven Goldsmith’s article, “A Civil Action: UW Law School tries to right a historic wrong” (University of Washington Magazine, December 2000), online here. I also used the March 2001 induction ceremony by the Washington Supreme Court, which were reported and which were provided to me by the court. The Washington Supreme Court’s 1902 decision denying Yamashita’s petition for admission to the bar is online here.